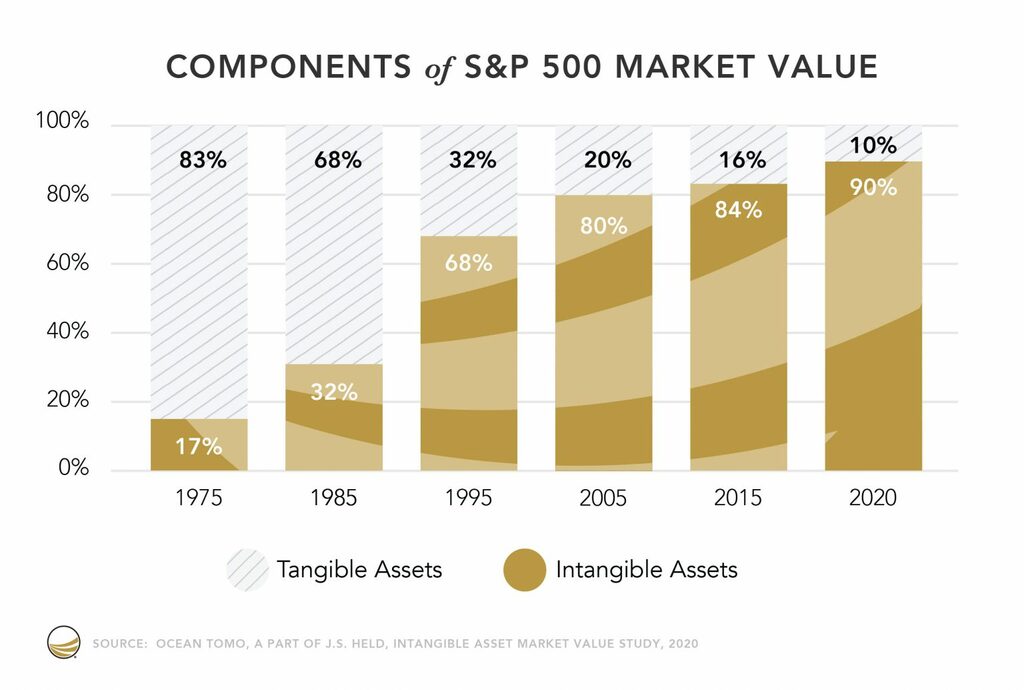

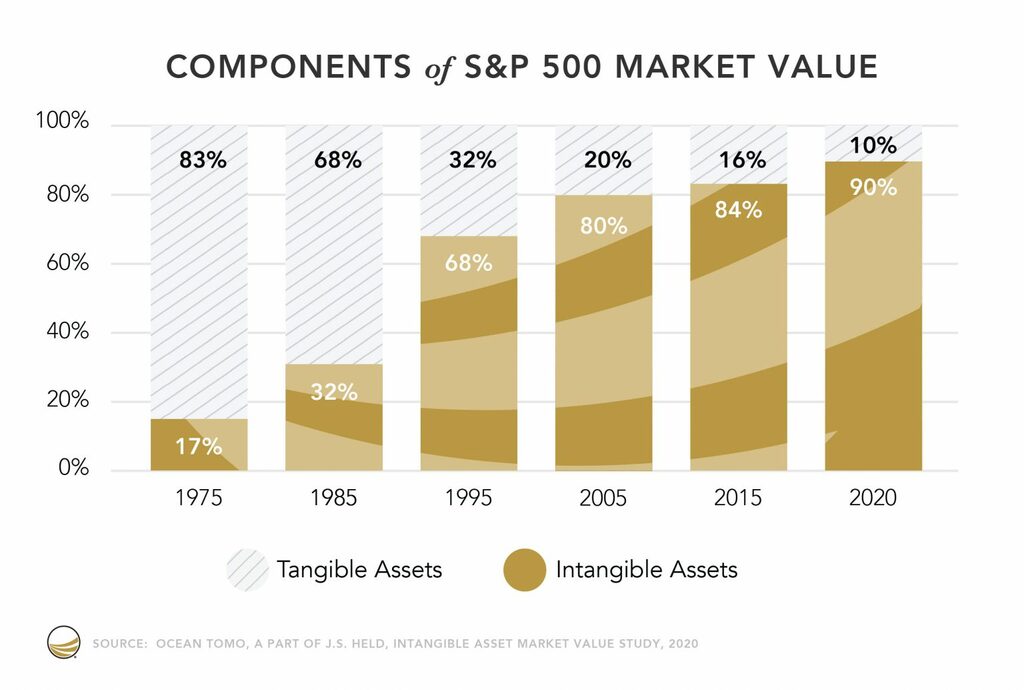

In the past 4 decades, intangible value has risen from 17% of enterprise value in the S&P 500 to over 90% currently.

Who should manage IP? Often it falls to the lawyers. But is this the best approach?

I don’t want to embarrass lawyers, but are they the best people to even ask about your IP?

Let’s examine it.

How much IP do you need to study to become a lawyer?

In Europe it can take 4 years to achieve a bachelor’s degree in law. Entry to study for the law degree can be immediately after completing secondary school (high school). In the USA, it takes typically 3 years of fulltime study to get a JD (Juris Doctor) degree. The entry requirements usually require a bachelor’s degree. The original major can be in subjects such as arts, science or engineering.

And while the training for a law degree is intensive, rich and deep, it cannot cover every aspect of law.

There isn’t a standard syllabus. Typically the first year will start with common core subjects and students will branch out in subsequent years. For example, Georgetown University in Washington DC offers first year students courses in civil procedure, constitutional law, criminal justice, legal practice, property, torts and a first-year elective.

Once the basics are covered, students can select different streams of specialisation from second year onward.

In Harvard Law School the current programs of study are:

- criminal law and policy

- international and comparative law

- law and business

- law and government

- law and history

- law and social change

- law, science and technology.

With so much diversity in legal studies, it is not possible for an undergraduate course to cover every single concept. If a student follows a public policy, political science, civil rights, tax law or environmental law route, IP-related modules will not even feature.

And even if a law student selects a technology or business law route, that might only involve one module of IP law (12-24 hours of lectures). The more immersive version might have 3 modules – one each of patents, trademarks and copyright – and still not cover the important area of trade secrets.

This week I asked a professor who teaches IP to LLM (masters) students. Many of his students have never taken an undergraduate IP module – and those are the ones who have chosen to specialise further with postgraduate IP qualification.

The surprising result is that most people who have studied for law degrees may never have studied a module of IP law. Furthermore, the small number who do, have probably had less than 36 hours of lectures on the topic.

Even at 36 hours, that is far less than the 10,000 hours that Professor Anders Ericsson postulated (and Malcolm Gladwell popularised) for mastery.

And it is certainly less than the 57,600 hours it takes to master IP strategy.

The upshot

The upshot is that it is a flawed assumption to expect that the average lawyer is particularly qualified to handle any IP matter. And yet, when there is an issue concerning intangible assets, the CEO will turn to the legal department to look after it.

Why is this a problem?

This takes us back to the graph (reproduced here for convenience).

If we are living in 1975, it doesn’t matter very much. If the intangible part is not handled in the most effective way, it only represents damage to a small fraction of the value. This could be masked by performance in the remaining 83% of the business.

But now, when intangible value represents 90% of the business, ineptitude in this area can have nine times more impact than any equivalent mishandling of the tangible part of the business.

This is not lawyer bashing

For everyone who thinks this is lawyer bashing, it is not.

This article is aimed squarely at the C-suite assumption that the lawyers are qualified to handle such precious assets.

Why are you taking the biggest part of the company’s value and placing it in the hands of the least entrepreneurial department? And will you still do it with the new knowledge that most lawyers weren’t trained to do anything with it either?

Why would a lawyer say “yes”?

Imagine, if you will, a company where the legal department is a cost centre with a budget of $10 million. Like all other departments, they are under pressure to control costs. Suddenly the company is faced with a $200 million opportunity or a $200 million problem. An opportunity or problem that is almost entirely intangible and with a large IP component.

When the company has a sudden opportunity or problem, they turn to the lawyer. Now the lawyer has 2 options:

- Say “Uhmm. I only studied this for 12 hours, and that was 10 years ago.”

- Say “Leave it to me”, research frantically and hope to take this chance to be a hero. After all, the lawyer is smarter than average and is at least as likely as anyone else to pick up the concepts.

A rational player will often select the second option.

And this even follows the oft-quoted advice from Richard Branson :

“If somebody offers you an amazing opportunity but you are not sure you can do it, say yes – then learn how to do it later!”

Richard Branson blog

And with an opportunity or problem of this size, there is now a budget to go externally for specialist counsel. These are lawyers who really do know something about IP.

If this is the lawyer’s first rodeo, it will be hard to figure out the details – who to engage, what to ask them and what outcome to expect from the process.

It is an expensive way to train the lawyer.

Pause for thought

If you are a CEO facing into a venture capital funding round, this can be a once-in-a-lifetime experience. You are at a disadvantage in terms of deal sophistication relative to the VC who has done hundreds of deals annually.

Similarly, a lawyer who is embarking on an IP licensing negotiation does not have the same expertise, instinct and skills as someone who has led hundreds of licensing engagements.

It is not a criticism of the lawyer. It is a simple reflection of the most common reality.

About the author:

Raymond Hegarty is an IP strategist, author and speaker. He is an IP coach to CEOs and CFOs of high-growth technology and life science companies.

He is the author of three bestselling books on IP strategy and has spoken to tens of thousands of people on topics of innovation and intellectual property. IAM Magazine has recognised him as one of the world’s top 300 IP strategists every year for the last 10 years.

He is the CEO of IntaVal, a leading global IP strategy consultancy.