The economic volatility and uncertainty is causing entrepreneurs is causing business owners to review their strategies and pivot. But what is a pivot?

A pivot is a fundamental shift in business strategy when you realise that your product or service does not meet the current needs of the market. The term was popularised by Eric Ries and Professor Steve Blank in their writing and teaching about the Lean Startup movement. Some examples of companies that became massively successful after pivoting are Flickr, YouTube and Twitter.

Pivot Case 1: Ludicorp

The gaming company Ludicorp was based originally in Vancouver, Canada. They developed Game Neverending as an online multiplayer game that was designed to never end.

A key concept of the game was that there was no winner or loser. Players could use a digital map to invent objects and trade them with other users.

One feature of the game was that it allowed users to exchange photos. Professional and amateur photographers began to adopt this as a way to upload, store and share high-resolution photographs. As digital cameras and camera phones proliferated, the demand for this service exploded.

This became the core of the popular photo sharing community, Flickr.

Pivot Case 2: Tune In, Hook Up

Tune In, Hook Up was one of many dating sites that sprung up on the internet. One of its features allowed users to upload self-created videos to introduce themselves. These videos could be ranked according to attractiveness and as a way of finding matches.

The online dating aspect did not catch on, but the company had developed some excellent video and uploading tools. This part of the business became popular beyond the dating realm.

The company changed its name to YouTube and the rest, as they say, is entrepreneurial history.

Pivot Case 3: Odeo

Odeo was a directory and search platform for RSS-syndicated audio and video sites. They built tools for creating and distributing Flash-based podcasts.

In 2005, they faced extinction because of the runaway success of Apple’s iTunes.

Based on employee suggestions gathered over 2 weeks, manager Jack Dorsey repurposed their internal messaging system and relaunched the service as Twitter.

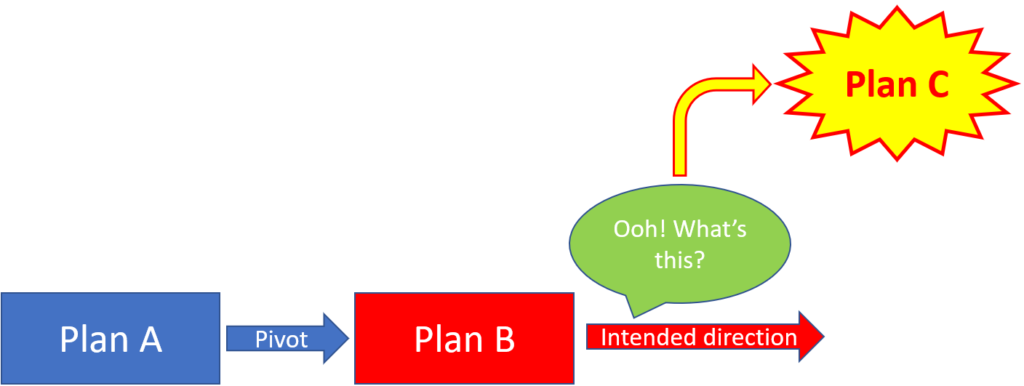

Entrepreneurial success is rarely linear

The path to entrepreneurial success often appears linear to external observers. But it is very rare that the final product is the fruit of Plan A. Often it is not even Plan B. The nimble entrepreneur learns from experiments and pivots.

But what do the pivots mean for patents and intellectual property?

What happens to IP in a pivot

Take a typical path for an entrepreneurial venture. The founders begin with an idea. They devote resources and energy to developing it. They may even develop some IP where they file a patent application or apply for a trademark. After pouring time, energy and money into the idea, they find that they are not getting traction.

So, they take the hard decision of scrapping Plan A and moving to Plan B.

Because of the effort committed to Plan A, there are not as many resources available for Plan B. But the team is more experienced and can run faster the second time round. Indeed, they have to run faster. Because there is not as much runway left.

And while they are working on Plan B they find that a small segment of customers become interested in a variant. It could be called Plan B’ or Plan C.

Plan C goes crazy. This takes off so quickly that developers must work around the clock to keep up with demand.

This pivot can lead to a success that far outstrips the original plan.

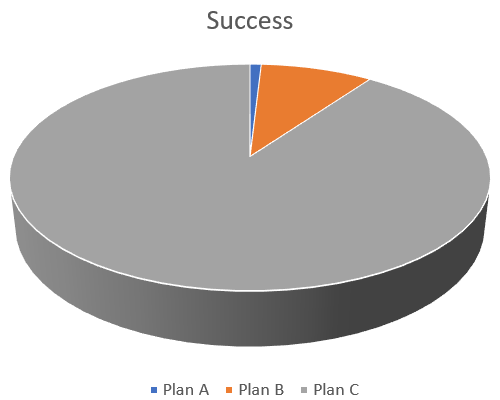

Let’s track the IP in this story

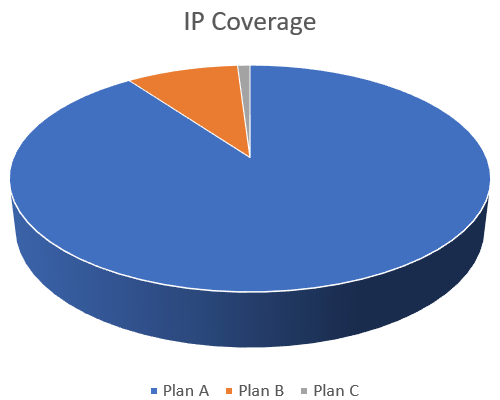

- 90% of the company’s formal IP is in Plan A.

- 9% of the company’s formal IP is in Plan B.

- There was no time to think about the IP for Plan C.

It is clear that the success of Plan C is far out of balance with its IP coverage.

How can IP be left behind?

Everyone knows instinctively that IP is important. But now they are running too quickly to keep up with customer demand. They rely on the belief that they can fix the IP later.

But now Plan C is 100x bigger than Plan A, so it is even a bigger challenge. It now becomes more important to fix. And probably much more expensive.

Case study: Facebook IPO vulnerability

In 2011, when Facebook was valued at $90 billion, the company had filed just 22 patent applications (10 granted and 12 pending).

Just weeks before Facebook’s IPO in 2012, Yahoo filed a patent infringement lawsuit against Facebook. At that time, Yahoo had more than a thousand patents.

One month later, Facebook bought a portfolio of 650 patents from Microsoft to strengthen its position before the IPO. That transaction cost the company $550 million. That is almost $850k per patent.

The upshot?

When your company finally finds success, you need to be vigilant that your success does not reveal vulnerabilities.

If you have not been building a strong IP position to support your new success, you may need to set aside reserves now to gain access to the rights you need.

If you need to explore your options, reach out to your IP coach here.

About the author:

Raymond Hegarty is an IP strategist, author and speaker. He is an IP coach to CEOs and CFOs of high-growth technology and life science companies.

He is the author of three bestselling books on IP strategy and has spoken to tens of thousands of people on topics of innovation and intellectual property. IAM Magazine has recognised him as one of the world’s top 300 IP strategists every year for the last 10 years.

He is the CEO of IntaVal, a leading global IP strategy consultancy.