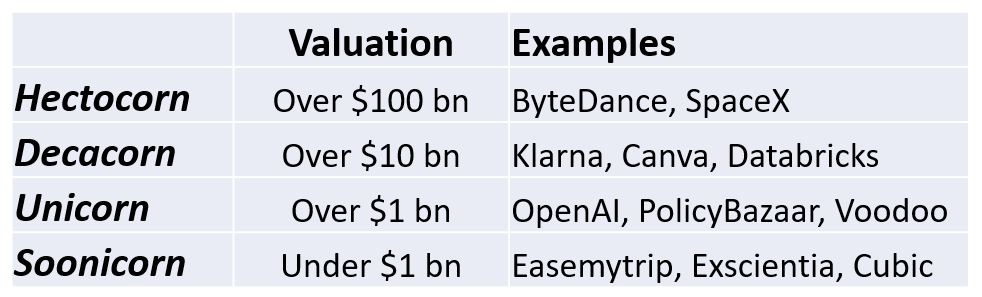

Unicorns, decacorns, hectocorns and soonicorns

It seems that every day that Business media is full of stories about unicorns these days. You may ask “What is a unicorn?”

A unicorn is a privately held company that is valued at a billion dollars or more. The term was coined by venture capitalist Aileen Lee in 2013. Because such companies are so rare as to be almost mythical, she introduced the concept of the “Unicorn Club” to describe them. In 2013 there were just 39 unicorn companies. In February 2022, according to CB Insights, there are exactly one thousand unicorn companies globally.

During the decade to 2013, 4 unicorns were born per year. In 2020, Gené Teare reported that this list is growing at a rate of about one new company every 3 working days. That rate accelerated to more than 1 per day in 2021 and the trend has continued into 2022.

Are unicorns eternal?

When a company goes public, it is no longer termed a unicorn. This could take the form of an exit via acquisition or IPO. Former unicorns include companies such as Uber, Facebook and AirBnB.

Also, obviously, if a company ceases trading or its value falls below a billion dollars, it will lose its unicorn status.

What is a decacorn?

A decacorn is an invented word combining “deca” (meaning ten) and “-corn” (from unicorn) to mean a privately held company whose value exceeds $10 billion. Currently there are 48 companies with a value of $10 billion or more.

Examples include Epic Games, Klarna, Instacart and Databricks.

Does that mean that there are private companies worth more than a hundred billion?

Yes, a hectocorn (“hecto” meaning hundred and “-corn” from unicorn) is a privately held company valued at more than $100 billion. Currently there are only 2 companies in that rarefied category – Bytedance and SpaceX. The Chinese company Bytedance, developer of artificial intelligence apps such as TikTok, is valued at $140 billion. SpaceX, the American aerospace company, is valued at just over $100 billion.

Stripe, the payments company, is not far outside this category with a valuation of $95 billion.

What is a soonicorn?

Whenever a business article mentions a funding round that has minted a new unicorn, the discussion leads to questions about which companies will be next. This has led to a new term – a “soonicorn”. A soonicorn is a privately-held company that is expected to become a unicorn, “soon.” A soonicorn is an exciting place to be. It has momentum, ambition and belief. If hectocorn is at the top of a pyramid, are far more soonicorns at the base of the pyramid.

In a nutshell, a unicorn is a company valued at over a billion dollars, a decacorn is a company valued at over 10 billion dollars and a hectocorn is a company valued at over 100 billion dollars. When a company ceases to be private (for example through acquisition or IPO) it is no longer a unicorn, decacorn or hectocorn.

The table below summarises differences:

Is it easy to become a unicorn?

First of all, let’s look at the mathematics:

How much is a million anyway?

When I was young, I learned that the big numerical steps were a hundred, a thousand, a million and then a billion. A billion was a million times a million (that is “bi-” meaning “two times” and “million”) – twelve zeroes. Then I heard Americans talking about a billion being a thousand million – meaning only nine zeroes.

It was all very confusing, so I had to research it. Since the 19th century, Americans used the word “billion” on the short scale to indicate 1,000,000,000 (109, or ten to the power of nine). In British English, the word “billion” had the long-scale meaning of 1,000,000,000,000 (1012, or ten to the power of twelve). This continued until the 1970s until British politicians agreed to harmonise the term.

Now most people understand the word “billion” to have the US meaning of 1,000,000,000, that is nine zeroes.

How easy is it to become a unicorn?

The original term unicorn was coined to elevate the status of those companies and identify them as being so rare that they are almost mythical. One of the downsides of this terminology is that it has created a familiar caricature from an almost unreachable mythical target. This familiarity has led people to think that it is easy to become a billion-dollar company. It even distorts mathematical logic.

The logic goes like this:

If you have succeeded in becoming a one-million-dollar company, the next logical step is to become a billion-dollar company.

But is it really as easy as that?

Don’t forget, a billion is a very big number

Imagine filling each seat on a Boeing 747 aircraft with one founder representing a million-dollar company. The combined values of their companies would still only total $366 million dollars. That is just over a third of the way to a billion dollars.

The growth path to a billion-dollar valuation

Let’s do a mathematical exercise:

If a startup company takes 2 years to grow to a valuation of $10,000 and then continues to grow by a respectable 10% every year, by the end of Year 10 it would be worth $214,359. At that growth rate, it would take 28 years to grow to a million. By year 88, it would be worth $362,886,593. That is a lot of money, but nowhere near a billion.

If the same startup company could double its value every two years and maintain that growth, by the end of Year 10, it would be worth $1.6 million. Even given the fact that compounding is a powerful force, it would be the 30th year before the value of such a rapidly-growing company would cross the billion-dollar valuation threshold.

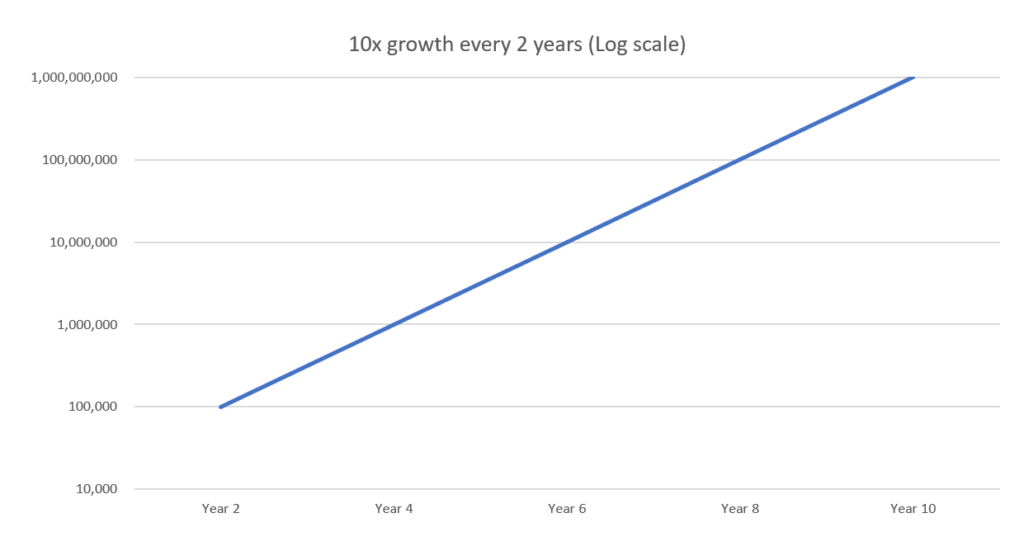

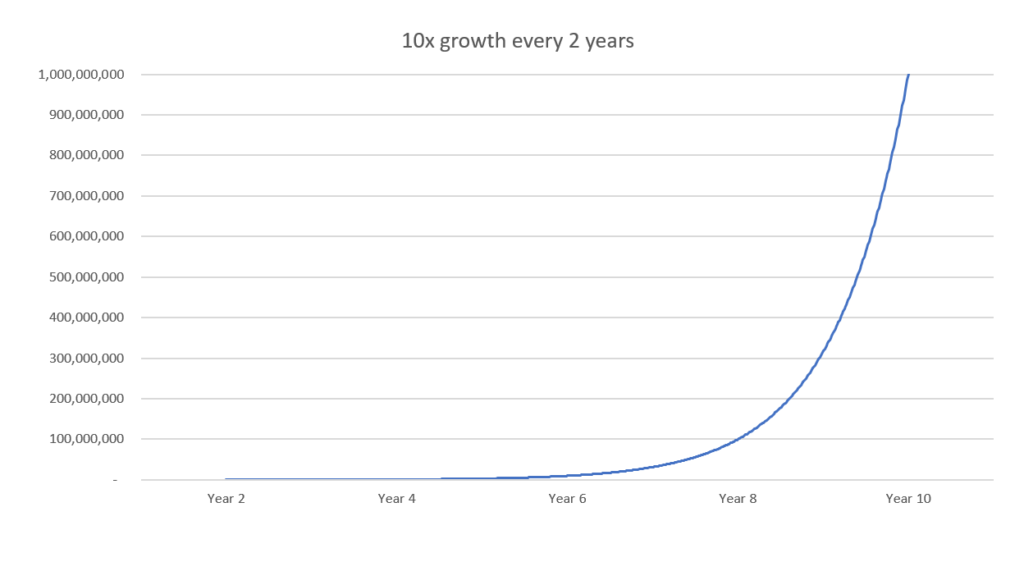

The third example in the table below is of a company that can build to unicorn status in 10 years by growing consistently at a rate of 10 times every two years.

Perhaps that rate of growth appears plausible, especially when natural progression of the numbers “a hundred, a thousand, a million and a billion” rolls off the tongue so easily.

It also looks plausible when the growth is mapped on a logarithmic scale:

The straight line on the logarithmic plot conceals the phenomenal growth that is more evident when graphed on a linear scale.

Achieving such consistent growth depends on multiple conditions, including:

- An offering valuable enough to satisfy an important market need

- Ability to disrupt the market

- Ability to withstand reaction by powerful incumbents

- Hospitable macroeconomic environment

- A market with sufficient capacity to absorb the growth

- Ample investment to fuel the growth

- Availability of talent at each level of scale

- Competence to manage massive growth without going off the rails

A unicorn is not just another horse.

Jessie “Unicorn” Moore said that unicorns eat delicious food such as rainbow cakes and jellybean pop tarts. If you want to see some recipes, you can find them at this link.

According to the Magical Unicorn Society in the UK, unicorns eat flowers such as Diamond Leaf Willow, Winky Wooh and Sacred Datura (“poisonous to all creatures except unicorns”). You can find a beautiful explanatory graphic on their website.

Based on such authority, if you were to feed a unicorn regular horse food, it would perish. It would be folly to ask someone only experienced in breeding and rearing horses to look after your unicorn.

Similarly, what it takes to build a million-dollar company is not the same as what it takes to run a billion-dollar company. The kind of scrappy, entrepreneurial innovation that builds a startup out of nothing requires a different set of skills from the governance and administration of a multi-billion-dollar organisation.

The strategic landscape is different

- A startup is focusing on survival, product development, trying to convince a skeptical market and attracting investment.

- A unicorn will have de-risked the startup phase and has overcome the hurdle of finding product-market fit.

The competitive environment is completely different. A startup company can operate largely beneath the radar until it becomes successful. A disruptive unicorn will face competition from the powerful incumbents while also watching out for the wannabe soonicorns who are snapping at its heels.

Also, because intangible value represents over 90% of enterprise for high-growth companies, It becomes especially important to manage IP strategy, intangible assets and IP risks to growth for these companies.

This will be covered in more depth in other articles.

About the author:

Raymond Hegarty is an IP strategist, author and speaker. He is an IP coach to CEOs and CFOs of high-growth technology and life science companies.

He is the author of three bestselling books on IP strategy and has spoken to tens of thousands of people on topics of innovation and intellectual property. IAM Magazine has recognised him as one of the world’s top 300 IP strategists every year for the last 10 years.

He is the CEO of IntaVal, a leading global IP strategy consultancy.